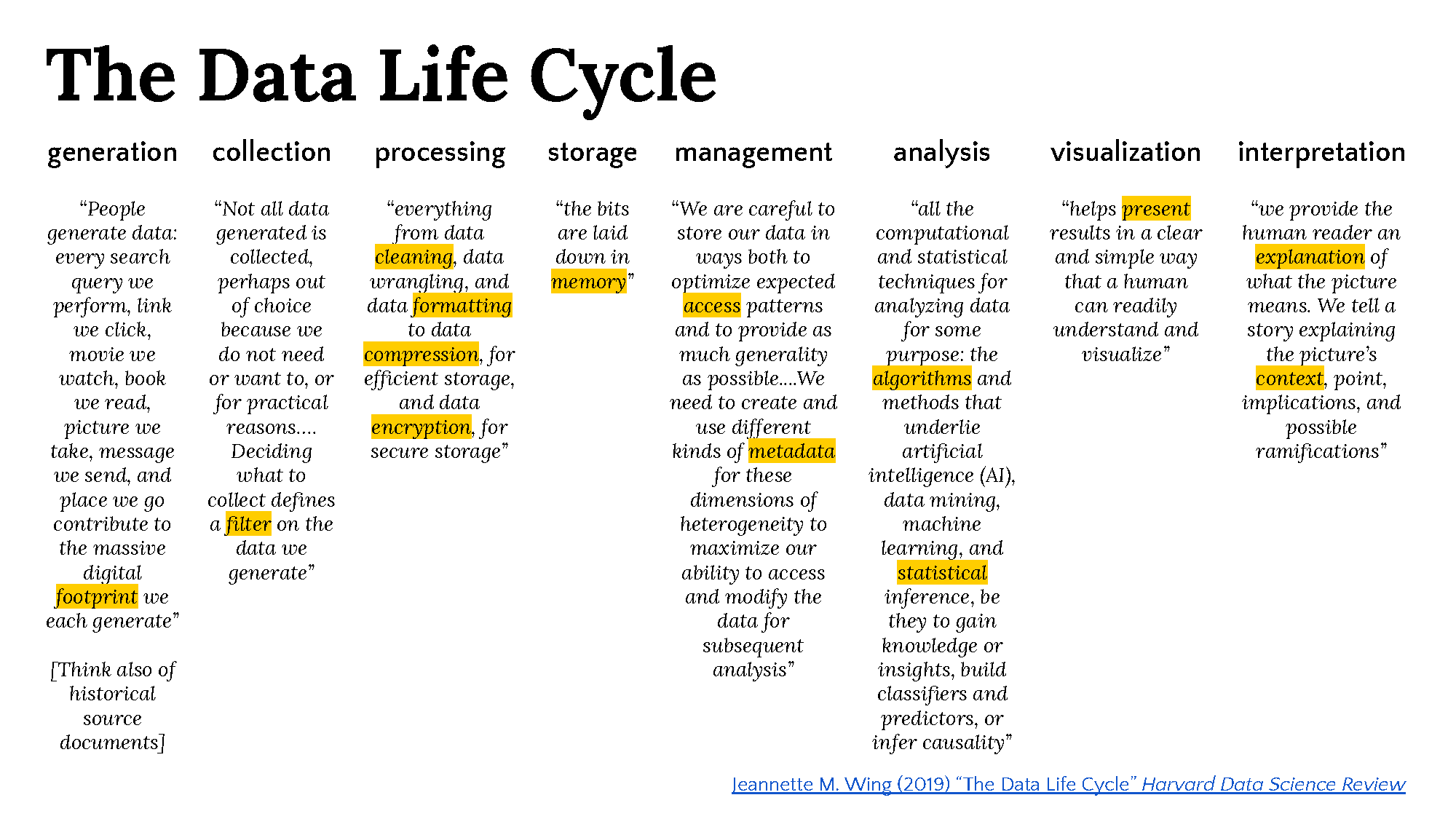

What is the data life cycle?#

Before our first session, we have 1 activity that we want you to do.#

What do you think about this framework? Do you find it helpful?

Does this framework change how you think about your data?

Take notes on your responses to this and we will discuss this in the session.

We will be discussing how to think like a data professional (scientist, journalist, etc.)? We will be applying this framework to a project.

The following is what we will do in our synchronous session#

Overview#

What is data? What forms does it take? What types are there?

How do we use data in DH?

How do we ask questions of data? How do we tell stories?

Data and power

Lessons for “big data”

Read more about the definition and practice of data science

Data in the humanities#

When we talk about data in the humanities, what do we mean? Big? Smart? Clean? Messy? Data in the Humanities

What is data ?#

What are the stages of data?

We begin without data. Then it is observed, or made, or imagined, or generated. After that, it goes through further transformations.

Forms of data#

There are many ways to represent data, just as there are many sources of data. After processing our data, we turn it into a number of products. For example:

Non-digital text (lab books, field notebooks)

Digital texts or digital copies of text

Spreadsheets

Audio

Video

Computer Aided Design/CAD

Statistical analysis (SPSS, SAS)

Databases

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and spatial data

Digital copies of images

Web files

Scientific sample collections

Matlab files & 3D Models

Metadata & Paradata

Data visualizations

Computer code

Standard operating procedures and protocols

Protein or genetic sequences

Artistic products

Curriculum materials

Collection of digital objects acquired and generated during research

List of forms adapted from: Georgia Tech Library

Raw data#

Raw data is yet to be processed, meaning it has yet to be manipulated by a human or computer. Received or collected data could be in any number of formats, locations, etc.. It could be in any of the forms listed above.

But “raw data” is a relative term, inasmuch as when one person finishes processing data and presents it as a finished product, another person may take that product and work on it further, and for them that data is “raw data”.

For example, is “big data” “raw data”? How do we understand data that we have “scraped”?

Processed/transformed#

Processing data puts it into a state more readily available for analysis, and makes the data legible. For instance it could be rendered as structured data. This can also take many forms, e.g., a table.

Here are a few you’re likely to come across, all representing the same data:

XML#

<Cats>

<Cat>

<firstName>Smally</firstName> <lastName>McTiny</lastName>

</Cat>

<Cat>

<firstName>Kitty</firstName> <lastName>Kitty</lastName>

</Cat>

<Cat>

<firstName>Foots</firstName> <lastName>Smith</lastName>

</Cat>

<Cat>

<firstName>Tiger</firstName> <lastName>Jaws</lastName>

</Cat>

</Cats>

JSON#

{"Cats":[

{ "firstName":"Smally", "lastName":"McTiny" },

{ "firstName":"Kitty", "lastName":"Kitty" },

{ "firstName":"Foots", "lastName":"Smith" },

{ "firstName":"Tiger", "lastName":"Jaws" }

]}

CSV#

First Name,Last Name/n

Smally,McTiny/n

Kitty,Kitty/n

Foots,Smith/n

Tiger,Jaws/n

Data formats#

A small detour to discuss (the ethics of?) data formats. For accessibility, future-proofing, and preservation, keep your data in open, sustainable formats. A demonstration:

If you click on this link, and then click on the Download option on the right hand side of the page, this will download a .Zip file. the Zip file contains 2 files named cats.

Open cats.csv file in a text editor, and then in an app like Excel. This is a CSV, an open, text-only, file format.

Now try to do the same with cats.xlsx. This is a proprietary format!

Sustainable formats are generally unencrypted, uncompressed, and follow an open standard. A small list:

ASCII

PDF

.csv

FLAC

TIFF

JPEG2000

MPEG-4

XML

RDF

.txt

.r

How do you decide the formats to store your data when you transition from ‘raw’ to ‘processed/transformed’ data? What are some of your considerations?

Tidy data#

There are guidelines to the processing of data, sometimes referred to as Tidy Data.1 One manifestation of these rules:

Each variable is in a column.

Each observation is a row.

Each value is a cell.

Look back at our example of cats to see how they may or may not follow those guidelines. Important note: Some data formats allow for more than one dimension of data! How might that complicate the concept of Tidy Data?

{"Cats":[

{"Calico":[

{ "firstName":"Smally", "lastName":"McTiny" },

{ "firstName":"Kitty", "lastName":"Kitty" }],

"Tortoiseshell":[

{ "firstName":"Foots", "lastName":"Smith" },

{ "firstName":"Tiger", "lastName":"Jaws" }]}]}

1Wickham, Hadley. “Tidy Data”. Journal of Statistical Software.

How do you find data for DH projects ?#

“What are the differences between data, a dataset, and a database?

Data are observations or measurements (unprocessed or processed) represented as text, numbers, or multimedia.

A dataset is a structured collection of data generally associated with a unique body of work.

A database is an organized collection of data stored as multiple datasets. Those datasets are generally stored and accessed electronically from a computer system that allows the data to be easily accessed, manipulated, and updated. Definition via USGS

Remember that just because data may be avaible digitally, it does not automatically exist as a dataset. You may have to do works manually (copying and pasting into a spreadsheet) or computationally (scraping the data) to create a dataset usable for computational analysis.

Read more about Data Prep and Cleaning and Cleaning Text Data

You can search for already existing datasets in the following library databases.

DH and data#

How might DH approach data? What’s special about DH data?#

“Those of us who are interested in seeing more robust cultural critique need to be more specific about where the intervention might most productively take place. It’s not only about shifting the focus of projects so that they feature marginalized communities more prominently; it’s about ripping apart and rebuilding the machinery of the archive and database so that it doesn’t reproduce the logic that got us here in the first place…. What would maps and data visualizations look like if they were built to show us categories like race as they have been experienced, not as they have been captured and advanced by businesses and governments? (Posner, 2015)

“What is needed is not a set of applications to display humanities “data” but a new approach that uses humanities principles to constitute capta [constructed knowledge, taken not given] and its display…. I am not suggesting that we simply introduce a quantitative analysis of qualitative experience into our data sets. I am suggesting that we rethink the foundation of the way data are conceived as capta by shifting its terms from certainty to ambiguity and find graphical means of expressing interpretative complexity.” (Drucker, 2011)

“Understanding how the humanities have traditionally approached big problems can inform how experts in data science can model meaningful conclusions based on the same skillful concern with answering questions based on a serious inquiry. Humanists, after all, are experts at probing the largest questions of our species…. The particular skills of humanities scholarship take many forms, but they all agree in emphasizing serious engagement with texts and their contexts.” (Guldi, 2019)

What kind of DH data?#

Big (Kaplan, 2015)

Small (Klienmann, 2016)

Micro (Risam & Edwards, 2017)

Smart (Schöch, 2013)

Ambiguous

Gender & race (Posner, 2015; McPherson, 2012)

Historical geographic information (Plewe 2002)

Research Questions: Data in the humanities#

Discussion#

What are some forms of data you use in your work?

What about forms of data that you produce as your output?

Perhaps there are some forms that are typical of your field?

Where do you usually get your data from?

Thinking like a Research Scientist#

When we discuss using data in humanities research, what questions do we need to ask about our data sets?

Do those sets even exist?

Are they openly accessible?

What restrictions might we encounter?

Ethical

Legal

Copyright

Licensing

Format

Cleanliness

What ethical considerations might ensue? Institutional Review Boards (IRB) are meant to provide oversight for research studies (involving human subjects). Are IRBs sufficient, or are there additional considerations?

What does it mean to use data collected for one purpose for a different purpose? What is left out?

What humanities questions can you ask?

Big data, medium data, small data, curated data, clean data

Humanities Data in the Library: Integrity, Form, Access by Thomas Padilla

“Where traditional library objects like books, images, and audio clips begin to be explored as data, new considerations of integrity, form, and access come to the fore. Integrity refers to the documentation practices that ensure data are amenable to critical evaluation. Form refers to the formats and data structures that contain data users need to engage in a common set of activities. Access refers to technologies used to make data available for use.”

“To what extent is information about humanities data collection provenance, processing, and method of presentation available to the user?” (Posner cited by Padilla)

“To what extent are data and the code that generates data available to the user?” (Stodden cited by Padilla)

“To what extent are the motivations driving all of the above available to the user?” (Risam cited by Padilla)

Handout for data discussion#

Data and power#

What are the potentials of using data to solve problems or to advance research? What are the big problems or limitations?

Different points of view#

Data as liberation#

“Liberation technology enables citizens to report news, expose wrongdoing, express opinions, mobilize protest, monitor elections, scrutinize government, deepen participation, and expand the horizons of freedom. But authoritarian states such as China, Belarus, and Iran have acquired (and shared) impressive technical capabilities to filter and control the Internet, and to identify and punish dissenters. Democrats and autocrats now compete to master these technologies. Ultimately, however, not just technology but political organization and strategy and deep-rooted normative, social, and economic forces will determine who ‘wins’ the race.” (Diamond, 2012)

Data as advocacy, evidence#

Advocacy through data (e.g., Visualizing Information for Advocacy, 2013)

Open/civic data

As government accountability/transparency (Hoffman, 2012)

BUT depends on volunteer labor, often addressed to governments and NGOs (Hooker, 2018) and belongs to the “data economy,” rather than being an act of critical transparency (Birchall, 2015)

“The data sets that make up Big Data are always creations of human design, and thus are always implicated in social relations and power dynamics (Andrejevic, 2014; boyd and Crawford, 2012; Crawford et al., 2014; Van Dijk, 2014). In these critical analyses, the ‘real’ value of (big) data lies not so much in its incarnation of a new scientific method or paradigm; rather, its value is framed in terms of political power, insofar as it enhances various forms of government surveillance (Bauman and Lyon, 2013), and in terms of monetary resource, as it benefits corporate profit (Fuchs, 2010).” (Sharon & Zandbergen, 2017)

Data as extraction#

“U.S. intellectual-property law, established as an economic incentive for inventors, privileges people who can write. In copying down the grammar, the stories, and the vocabulary of the Penobscot, Siebert made them his. In dying, he made them the American Philosophical Society’s….Siebert’s approach as archetypal of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century anthropological research, which tended to cast indigenous people not as participants but as objects of study, and rarely aspired to benefit them.” -How Did a Self-Taught Linguist Come to Own an Indigenous Language? & Wayback link

“The Te Hiku team see data as the final frontier for colonisation. “They suppressed our languages and physically beat it out of our grandparents,” Jones says. “And now they want to sell our language back to us as a service.”Māori are trying to save their language from Big Tech & Wayback linkk

Examples of data resistance#

Group/participatory analysis of data (Jackson, 2008)

Quantified/quantifying self movement (Sharon & Zandbergen, 2017)

Data activism, both proactive & reactive (Milan & Van Der Velden, 2016)

“While digital humanists develop tools, data, and metadata critically…rarely do they extend their critique to the full register of society, economics, politics, or culture. How the digital humanities advances, channels, or resists today’s great postindustrial, neoliberal, corporate, and global flows of information-cum-capital is thus a question rarely heard in the digital humanities associations, conferences, journals, and projects with which I am familiar. Not even the clichéd forms of such issues—for example, ‘the digital divide,’ ‘surveillance,’ ‘privacy,’ ‘copyright,’ and so on—get much play.” (Liu, 2012)

Lessons for “big data”#

What are the potentials? What are the big problems?#

“We define Big Data as a cultural, technological, and scholarly phenomenon that rests on the interplay of:

Technology: maximizing computation power and algorithmic accuracy to gather, analyze, link, and compare large data sets.

Analysis: drawing on large data sets to identify patterns in order to make economic, social, technical, and legal claims.

Mythology: the widespread belief that large data sets offer a higher form of intelligence and knowledge that can generate insights that were previously impossible, with the aura of truth, objectivity, and accuracy.” (boyd & Crawford, 2012)

“The next time you hear someone talking about algorithms, replace the term with ‘God’ and ask yourself if the meaning changes. Our supposedly algorithmic culture is not a material phenomenon so much as a devotional one….It gives us an excuse not to intervene in the social shifts wrought by big corporations like Google or Facebook or their kindred, to see their outcomes as beyond our influence [and] it makes us forget that particular computational systems are abstractions, caricatures of the world, one perspective among many. The first error turns computers into gods, the second treats their outputs as scripture.” (Bogost, 2015)

“We believe ‘big data’ research can be similarly improved by working with, rather than denying the importance of, ‘small data’ (Kitchin and Lauriault, 2014; Thatcher and Burns, 2013) and other existing approaches to research….Furthermore, doing critical work with ‘big data’ involves understanding not only data’s formal characteristics, but also the social context of the research amidst shifting technologies and broad social processes. Done right, ‘big’ and small data utilized in concert opens new possibilities: topics, methods, concepts, and meanings for what can be understood and done through research.” (Dalton & Thatcher, 2014)

Ten simple rules for responsible big data research#

Acknowledge that data are people and can do harm

Recognize that privacy is more than a binary value

Guard against the reidentification of your data

Practice ethical data sharing

Consider the strengths and limitations of your data; big does not automatically mean better

Debate the tough, ethical choices

Develop a code of conduct for your organization, research community, or industry

Design your data and systems for auditability

Engage with the broader consequences of data and analysis practices

Know when to break these rules

Zook, Matthew et al. “Ten simple rules for responsible big data research.” PLoS computational biology vol. 13,3 e1005399. 30 Mar, 2017. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005399

Checklists, principles, examples#

Ethical issues around large data sets.#

This years’ racist chatbot: AI Trained on 4Chan Becomes ‘Hate Speech Machine’;

“On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” lays out the risks of large language models—AIs trained on staggering amounts of text data. These have grown increasingly popular—and increasingly large—in the last three years. They are now extraordinarily good, under the right conditions, at producing what looks like convincing, meaningful new text—and sometimes at estimating meaning from language. But, says the introduction to the paper, “we ask whether enough thought has been put into the potential risks associated with developing them and strategies to mitigate these risks.”

Timnit Gebru and Google

We read the paper that forced Timnit Gebru out of Google. Here’s what it says.

“… a system called GPT-3. It had ingested more training data than BERT and could generate impressively fluid text in genres spanning sonnets, jokes, and computer code. Some investors and entrepreneurs predicted that automated writing would reinvent marketing, journalism, and art.These new systems could also become fluent in unsavory language patterns, coursing with sexism, racism, or the tropes of ISIS propaganda. Training them required huge collections of text—BERT used 3.3 billion words and GPT-3 almost half a trillion—which engineers slurped from the web, the most readily available source with the necessary scale. But the data sets were so large that sanitizing them, or even knowing what they contained, was too daunting a task.(italics added) It was an extreme example of the problem Gebru had warned against with her Datasheets for Datasets project. - What Really Happened When Google Ousted Timnit Gebru.

Disciplines that may be of interest: STS, ethical AI

About your data project#

What topic(s) do you want to focus on?

What kind(s) of data will you need?

Do you already have a data set identified for use?

Here is is a link to our Datasets and Data Repositories guide

-

This version of the handout has additional content. Download the PDF for links to be active; they are not active when you view the file online.

Reflection (What to do after this session)#

What would you put about your data in your timeline? When considering the data life cycle are there certain places that might present challenges to your research project

How might good project planning help you overcome some of those challenges?

Refer back to the Project Charter handout? and add your notes.

Note: For the purposes of getting started with DH, we recommend finding an already existing data set for your project, as creating, cleaning and/or structuring a new dataset is often time and labor intensive.

Further Activities (optional)#

How did they make this?: Data storytelling and visualizations

Go to The Pudding and read one of their data journalism pieces.

In their archive, you can choose by topic or type of chart, based on your interests.

Once you have read an article, put the link in Slack, as well as some of your reflections. (One of us will post an example response in Slack that you can use as a template.)

As you read, pay special attention to the following questions:

Their data#

Where did their data come from?

Is the data public?

How big was the data? Did they use all of it?

Their analysis#

What is their thesis statement?

What was their hypothesis?

What choices did they make as the analysis developed?

Were there caveats or ramifications to their choices?

What were their conclusions?

Their visualizations#

What types of visualizations did they use?

Did the visualization help or hurt the arguments they made?

Was the visualization distracting or confusing?

Could you make a similar (if more simple) visualization?

Overall#

Did you think the article was interesting?

Did having data to back up their thesis statement help make their argument?

Further reading: This 3-part series on data journalism and data projects in general.

Optional extra viewing to see how Vox:Earworm did another collaborative project: We tracked what happens after TikTok songs go viral

Attribution#

Session Leaders: Rafia Mirza

Written by Rafia Mirza.

Primarily based on Chris Alen Sula’s work.“Nuances of Data: What Can DH Contribute?” Association for Computers & Humanities, Pittsburgh, Penn., 24 July 2019.

Additional content from:

Some content from Eric Godat & Robert Kalescky DS 1300 class

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.