Data Life Cycle#

Introduction to the stages of the Data Life Cycle#

When we talk about data, what do we mean?

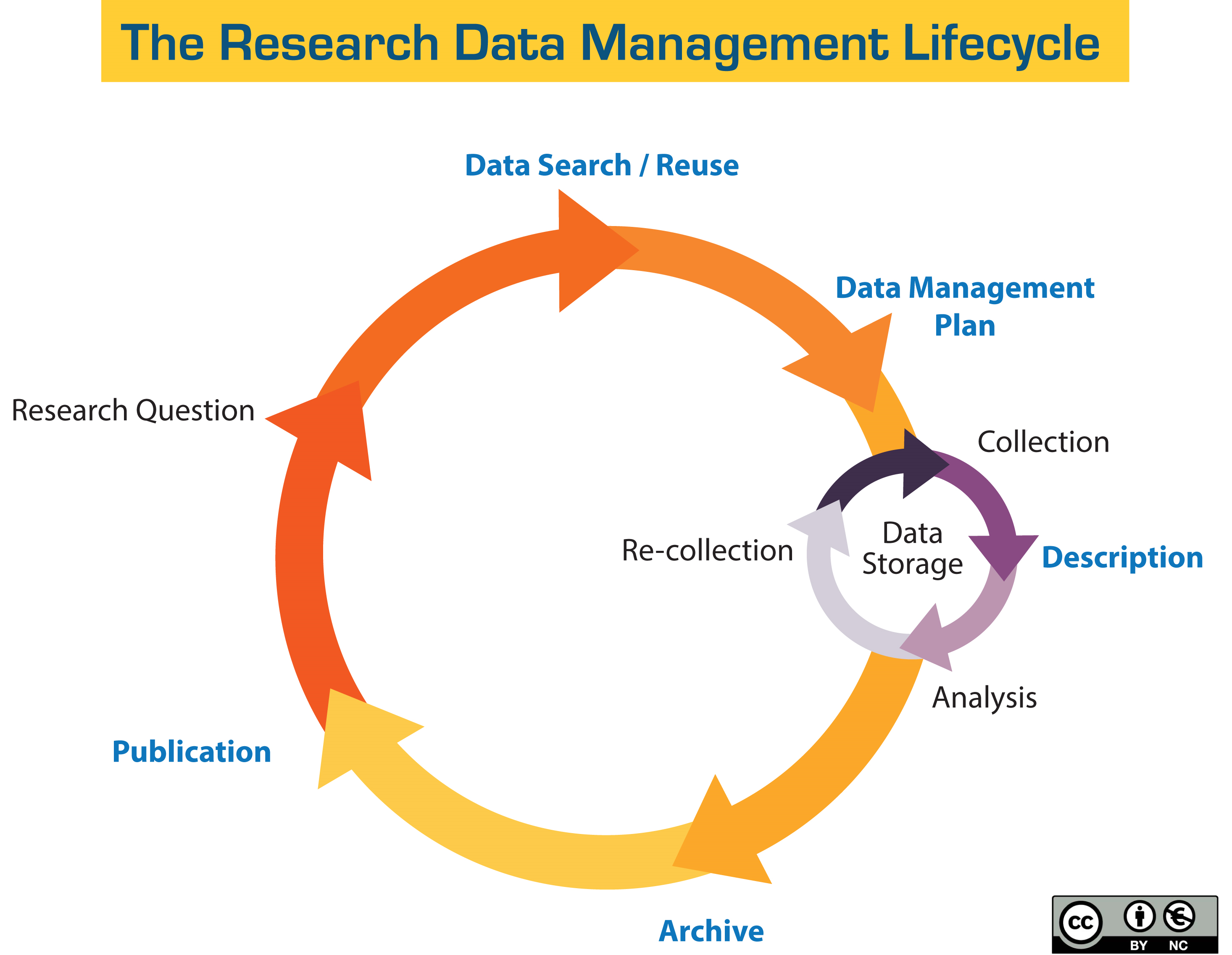

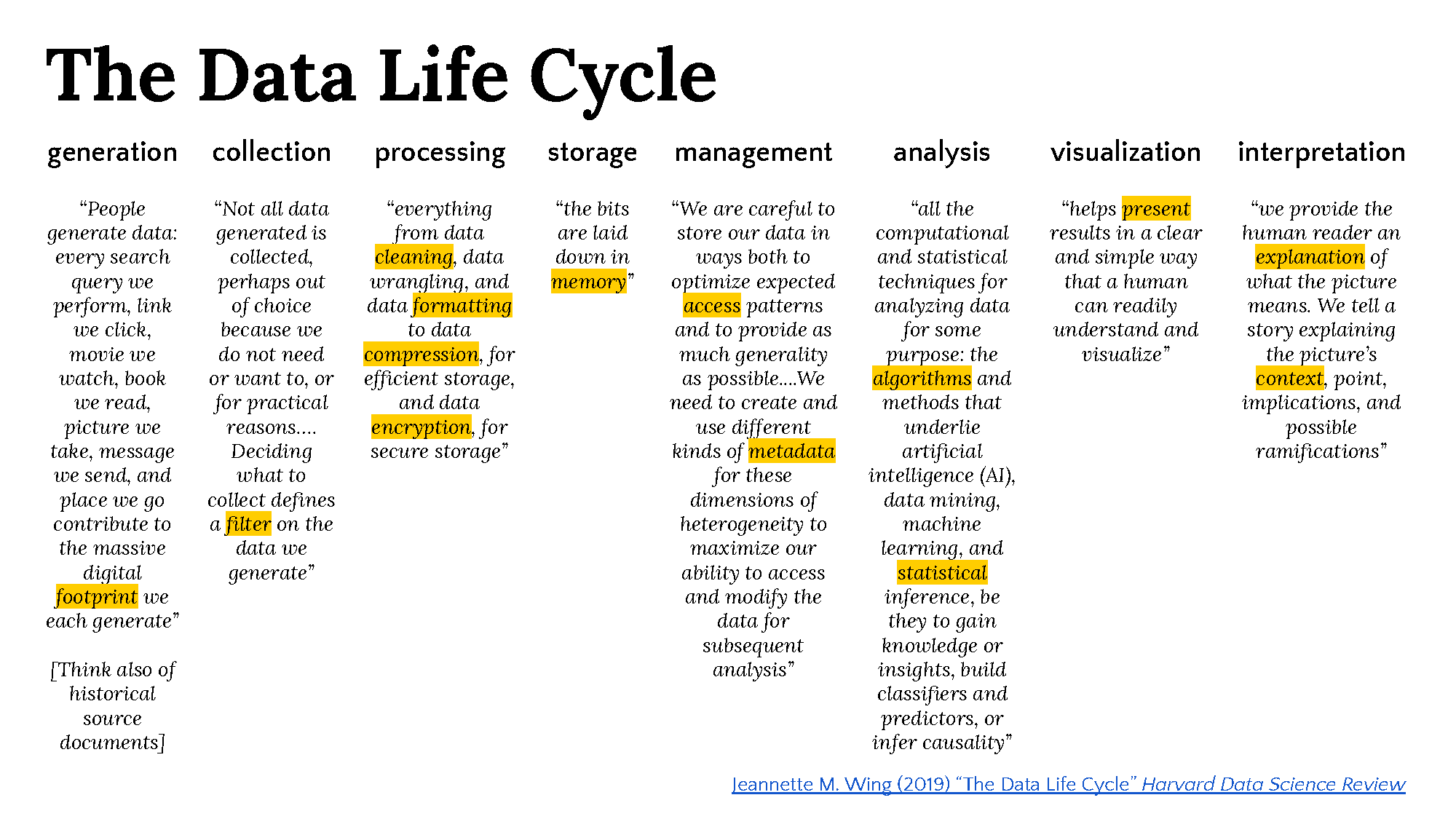

What is the data life cycle? Where are you on this cycle? Which steps apply to you?

We are discussing these steps as a list, which may make you think of them as sequential, however: you may skip some steps, you may go back and forth between various steps - it all depends on what you are trying to do and what your role in your current research project is.

Discussion topic: In your experience, how does this relate to other research frameworks: e.g. Research Process, Research Life Cycle, Scientific Method, etc. What steps in those process are similar to what we are discussing for the Data Life Cycle.

Research questions

Why are you looking for data? What kind of data do you think will have useful information for your questions?

Data Search/ Reuse

You are looking for already existing data or data sets that you can reuse for your research.

What is the difference between data and a data set?

Is the data you found in the proper format for analysis?

Is is clean and structured?

Data Management Plan (DMP)

Do you need a long term plan to manage your data?

Do you want to share it with others?

Does the grant you are working on require you have a plan for sharing and/or preserving your data?

Data Storage (Collection, Description, Recollection)

Where are you going to store the data?

Do you want to store the description/metadata?

Analysis

You are deciding what tools (Excel) or Scripts (Python, R) to use to on your data to ask questions.

Archive

You are done using the data, but you want to save it for the long term.

Publications

You are now publishing your results, research and/or the data set.

Data visualizations are a type of publication.

Additional Resources:

What do you think about this framework? Do you find it helpful?

Does this framework change how you think about your data?

Take notes on your responses to this and we will discuss this in the session.

We will be discussing how to think like a data professional (scientist, journalist, etc.)? We will be applying this framework to a project.

What is Data ?#

What are the differences between data, a dataset, and a database?#

“Data are observations or measurements (unprocessed or processed) represented as text, numbers, or multimedia.

A dataset is a structured collection of data generally associated with a unique body of work.

A database is an organized collection of data stored as multiple datasets. Those datasets are generally stored and accessed electronically from a computer system that allows the data to be easily accessed, manipulated, and updated.”

Forms of Data#

There are many ways to represent data, just as there are many sources of data. After processing our data, we turn it into a number of products. For example:

Non-digital text (lab books, field notebooks)

Digital texts or digital copies of text

Spreadsheets

Audio

Video

Computer Aided Design/CAD

Statistical analysis (SPSS, SAS)

Databases

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and spatial data

Digital copies of images

Web files

Scientific sample collections

Matlab files & 3D Models

Metadata & Paradata

Data visualizations

Computer code

Standard operating procedures and protocols

Protein or genetic sequences

Artistic products

Curriculum materials

Collection of digital objects acquired and generated during research

Adapted from: Georgia Tech Library Guide

Discussion: Forms of Data#

These are some (most!) of the shapes your research data might transform into. What are some forms of data you use in your work? What about forms of data that you produce as your output? Perhaps there are some forms that are typical of your field? Where do you usually get your data from?

Stages of Data#

We begin without data. Then it is observed, or made, or imagined, or generated. After that, it goes through further transformations:

Raw#

Raw data is yet to be processed, meaning it has yet to be manipulated by a human or computer. Received or collected data could be in any number of formats, locations, etc.. It could be in any of the forms listed above.

But “raw data” is a relative term, inasmuch as when one person finishes processing data and presents it as a finished product, another person may take that product and work on it further, and for them that data is “raw data”.

Discussion: Raw Data#

For example, is “big data” “raw data”? How do we understand data that we have “scraped”?

Processed/Transformed#

Processing data puts it into a state more readily available for analysis, and makes the data legible. For instance it could be rendered as structured data. This can also take many forms, e.g., a table.

Here are a few you’re likely to come across, all representing the same data:

XML#

<Cats>

<Cat>

<firstName>Smally</firstName> <lastName>McTiny</lastName>

</Cat>

<Cat>

<firstName>Kitty</firstName> <lastName>Kitty</lastName>

</Cat>

<Cat>

<firstName>Foots</firstName> <lastName>Smith</lastName>

</Cat>

<Cat>

<firstName>Tiger</firstName> <lastName>Jaws</lastName>

</Cat>

</Cats>

JSON#

{"Cats":[

{ "firstName":"Smally", "lastName":"McTiny" },

{ "firstName":"Kitty", "lastName":"Kitty" },

{ "firstName":"Foots", "lastName":"Smith" },

{ "firstName":"Tiger", "lastName":"Jaws" }

]}

CSV#

First Name,Last Name/n

Smally,McTiny/n

Kitty,Kitty/n

Foots,Smith/n

Tiger,Jaws/n

The importance of using open data formats#

A small detour to discuss (the ethics of?) data formats. For accessibility, future-proofing, and preservation, keep your data in open, sustainable formats. A demonstration:

Open [this file](Download cats.csv ) in a text editor, and then in an app like Excel. This is a CSV, an open, text-only, file format.

Now try to do the same with [this one](Download cats.csv. This is a proprietary format!

Sustainable formats are generally unencrypted, uncompressed, and follow an open standard. A small list:

ASCII

PDF

.csv

FLAC

TIFF

JPEG2000

MPEG-4

XML

RDF

.txt

.r

Discussion: Processed/Transformed#

How do you decide the formats to store your data when you transition from ‘raw’ to ‘processed/transformed’ data? What are some of your considerations?

Tidy Data#

There are guidelines to the processing of data, sometimes referred to as Tidy Data.1 One manifestation of these rules:

Each variable is in a column.

Each observation is a row.

Each value is a cell.

Look back at our example of cats to see how they may or may not follow those guidelines. Important note: some data formats allow for more than one dimension of data! How might that complicate the concept of Tidy Data?

{"Cats":[

{"Calico":[

{ "firstName":"Smally", "lastName":"McTiny" },

{ "firstName":"Kitty", "lastName":"Kitty" }],

"Tortoiseshell":[

{ "firstName":"Foots", "lastName":"Smith" },

{ "firstName":"Tiger", "lastName":"Jaws" }]}]}

1Wickham, Hadley. “Tidy Data”. Journal of Statistical Software.

Group Watch:#

We will watch this as a group and discuss the stages of the data lifye cycle for this research question:We measured pop music’s falsetto obsession - Vox Earworm

Optional extra: “Along the way, we discovered that using [social media platform] data to concretely answer this question is quite a challenge. Our process included creating dozens of custom data sets, careful fact-checking, and conversations with hit songwriters and music industry executives to match data with real experiences.”-We tracked what happens after TikTok songs go viral

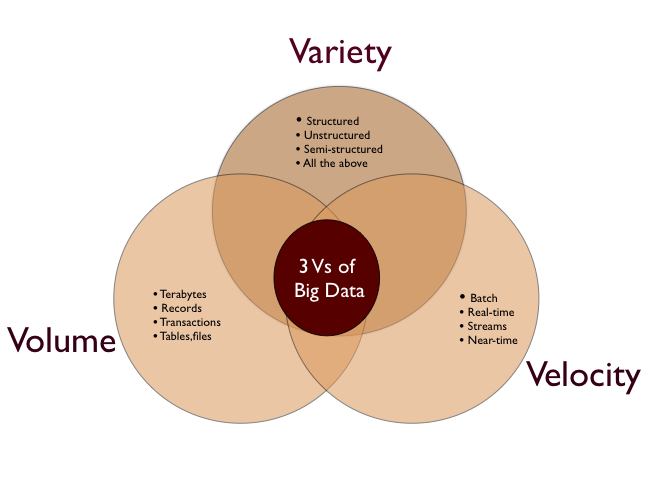

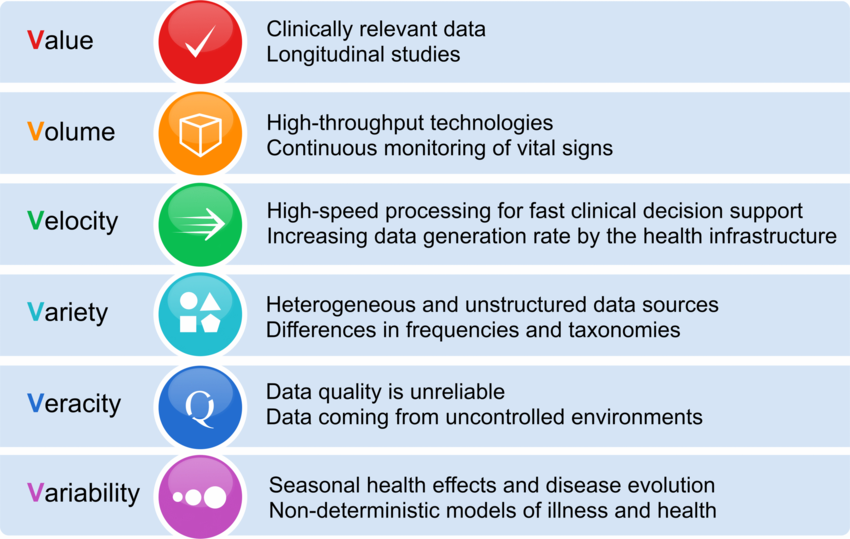

Big data#

What are the potentials of big data? What are the big problems?#

“We define Big Data as a cultural, technological, and scholarly phenomenon that rests on the interplay of:

Technology: maximizing computation power and algorithmic accuracy to gather, analyze, link, and compare large data sets.

Analysis: drawing on large data sets to identify patterns in order to make economic, social, technical, and legal claims.

Mythology: the widespread belief that large data sets offer a higher form of intelligence and knowledge that can generate insights that were previously impossible, with the aura of truth, objectivity, and accuracy.” (boyd & Crawford, 2012)

“The next time you hear someone talking about algorithms, replace the term with ‘God’ and ask yourself if the meaning changes. Our supposedly algorithmic culture is not a material phenomenon so much as a devotional one….It gives us an excuse not to intervene in the social shifts wrought by big corporations like Google or Facebook or their kindred, to see their outcomes as beyond our influence [and] it makes us forget that particular computational systems are abstractions, caricatures of the world, one perspective among many. The first error turns computers into gods, the second treats their outputs as scripture.” (Bogost, 2015)

“We believe ‘big data’ research can be similarly improved by working with, rather than denying the importance of, ‘small data’ (Kitchin and Lauriault, 2014; Thatcher and Burns, 2013) and other existing approaches to research….Furthermore, doing critical work with ‘big data’ involves understanding not only data’s formal characteristics, but also the social context of the research amidst shifting technologies and broad social processes. Done right, ‘big’ and small data utilized in concert opens new possibilities: topics, methods, concepts, and meanings for what can be understood and done through research.” (Dalton & Thatcher, 2014)

Ten simple rules for responsible big data research#

Acknowledge that data are people and can do harm

Recognize that privacy is more than a binary value

Guard against the reidentification of your data

Practice ethical data sharing

Consider the strengths and limitations of your data; big does not automatically mean better

Debate the tough, ethical choices

Develop a code of conduct for your organization, research community, or industry

Design your data and systems for auditability

Engage with the broader consequences of data and analysis practices

Know when to break these rules

Zook, Matthew et al. “Ten simple rules for responsible big data research.” PLoS computational biology vol. 13,3 e1005399. 30 Mar, 2017. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005399

Checklists, principles, examples#

Handout for data discussion#

About your data project#

What topic(s) do you want to focus on?

What kind(s) of data will you need?

[Data lifecycle handout]((https://raw.githubusercontent.com/SouthernMethodistUniversity/datalifecycle/main/files/handoutdlc.pdf)

(SouthernMethodistUniversity/datalifecycle)

(SouthernMethodistUniversity/datalifecycle)

(SouthernMethodistUniversity/datalifecycle)

(SouthernMethodistUniversity/datalifecycle)

Lessons for big data#

-

Download PDF for links to be active; they are not active when you view the file online.

Resources at SMU#

Glossaries#

References#

Andrejevic Mark. (2014). “The Big Data divide.” International Journal of Communication 8: 1673–1689.

Bauman, Z and Lyon, David. (2013). Liquid Surveillance. London: Polity Press.

Birchall, Clare (2015). “‘Data.gov-in-a-box’: Delimiting transparency.” European Journal of Social Theory 18 (2015): 185–202.

Bogost, Ian. 2015. “The cathedral of computation.” The Atlantic, January 15. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/01/the-cathedral-of-computation/384300/

boyd, d. & Crawford, K. (2012). “Critical questions for big data: Provocations for a cultural, technological, and scholarly phenomenon.” Information, Communication & Society 15(5): 662–679. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878

Crawford, Kate, Miltner K, and Gray M. (2014). “Critiquing Big Data: Politics, ethics, epistemology.” International Journal of Communication 8: 1663–1672.

D’Ignazio, Catherine & Klein, Lauren F. (2018). Workshop on Visualization for the Digital Humanities. IEEE VIS 2016. Baltimore, MD.

Dalton, Craig and Thatcher, Jim. (2014). “What does a critical data studies look like, and why do we care? Seven points for a critical approach to ‘big data.’” Society & Space. https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/what-does-a-critical-data-studies-look-like-and-why-do-we-care

Data Ethics Decision Aid (DEDA). Utrecht Data School https://dataschool.nl/deda/?lang=en

Diamond, Larry. (2010). “Liberation technology,” Journal of Democracy 21(3): 69–83.

Drucker, Johanna. 2011. “Humanities approaches to graphical display”, Digital Humanities Quarterly 5.1. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/5/1/000091/000091.html

Fuchs, Christian. (2010). “Labor in informational capitalism and on the internet.” The Information Society 26(3): 179–196.

Guldi, Jo. (2019). “What can the humanities teach us about Big Data?” History News Network https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/171186

Hoffmann, Leah. (2012). “Data mining meets city hall.” Communications of the ACM 55(6), 19–21. http://cacm.acm.org/magazines/2012/6/149784-data-mining-meets-city-hall/fulltext

Hooker, Sara (2018). “Why “sata for good” lacks precision,” Towards Data Science. https://towardsdatascience.com/why-data-for-good-lacks-precision-87fb48e341f1

Jackson, Suzanne F. (2008). “A participatory group process to analyze qualitative data,” Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action 2(2): 161–170.

Kaplan, Frédéric. (2015). “A map for big data research in digital humanities.” Frontiers in Digital Humanities https://doi.org/10.3389/fdigh.2015.00001

Kleinmann, Scott (2015). “Digital humanities projects with small and unusual data: Some experiences from the trenches,” Digital Humanities Now. https://digitalhumanitiesnow.org/2016/03/digital-humanities-projects-with-small-and-unusual-data-some-experiences-from-the-trenches/

Kitchin, Rob and Lauriault, Tracey. (2014). “Small data, data infrastructure and big data.” The Programmable City Working Paper 1. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2376148

Liu, Alan. (2012). “Where Is cultural criticism in the digital humanities?” In: Debates in the Digital Humanities, edited by Matthew K. Gold, 490–509. Minneapolis, Minn.: University Of Minnesota Press. http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/20.

McPherson, Tara. (2012). “Why are the digital humanities so white? or Thinking the histories of race and computation.” In: Debates in the Digital Humanities, edited by Matthew K. Gold, Minneapolis, Minn.: University Of Minnesota Press. https://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/read/untitled-88c11800-9446-469b-a3be-3fdb36bfbd1e/section/20df8acd-9ab9-4f35-8a5d-e91aa5f4a0ea.

Milan, Stefania, and Lonneke Van Der Velden. (2016). “The alternative epistemologies of data activism.” Digital Culture & Society 2(2): 57–74.

Plewe, Brandon. (2002). “The nature of uncertainty in historical geographic information.” Transactions in GIS 6(4): 431–456.

Posner, Miriam. (2016). “What’s next: The radical, unrealized potential of digital humanities.” Keystone DH Conference, University of Pennsylvania, July 22, 2015. http://miriamposner.com/blog/whats-next-the-radical-unrealized-potential-of-digital-humanities.

Redden, Joanna & Brand, Jessica. “Data harm record.” Data Justice Lab. https://datajusticelab.org/data-harm-record

Risam, Roopika & Edwards, Susan. (2017). “Micro DH: Digital humanities at the small scale” Digital Humanities 2017. https://dh2017.adho.org/abstracts/196/196.pdf

Schöch, Christof. (2013). “Big? Smart? Clean? Messy? Data in the humanities,” Journal of Digital Humanities 2(3). http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/2-3/big-smart-clean-messy-data-in-the-humanities/

Sharon, Tamar, and Zandbergen, Dorien. (2017). “From data fetishism to quantifying selves: Self-tracking practices and the other values of data.” New Media & Society 19(11): 1695–1709.

Tactical Tech Collective. (2013). Visualising Information for Advocacy. https://visualisingadvocacy.org

Burns, R., Thatcher, J. (2015) “Guest editorial: What’s so big about Big Data? Finding the spaces and perils of Big Data.” GeoJournal 80, 445–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-014-9600-8

Van Dijk, J. (2014). “Datafication, dataism, and dataveillance: Big Data between scientific paradigm and ideology.” Surveillance & Society 12(2): 197–208.

“Where things have gone wrong,” DEON. http://deon.drivendata.org/examples

Wing, Jeanette M. (2019). “The data life cycle.” Harvard Data Science Review 1. https://hdsr.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/577rq08d